Is It Easy to Sell Vanguard Etf

Monday evening, I was minding my own business when I saw something completely absurd.

Apparently, Vanguard was out defending ETFs against the accusation that they create untold market risks.

I was interested because, after all, I have fond memories of Vanguard. A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, my first investments were in a Vanguard mutual fund. There's some nostalgia there for me and perhaps due to that nostalgia, I've always kind of bought into the notion that the firm represented a bastion of sanity in an increasingly insane world.

So it wasn't the fact that the venerable firm was defending ETFs that was absurd. I was happy - indeed eager - to read what they had to say. Unfortunately, it turns out they're clueless. Or at least it certainly seems that way.

One thing I should note is that on Monday night, I wrote a colorful post on this subject complete with a classic Heisenberg vignette that I encourage you to read as a kind of colloquial version of what you'll read below.

If you follow my stuff, you're well aware of how I feel about corporate bond ETFs. And even if you don't read Heisenberg, you're probably aware that there's considerable debate about whether such ETFs offer true liquidity or whether they in fact only provide what we might call "phantom liquidity."

Carl Icahn and BlackRock Chief Larry Fink famously debated this issue a couple of years ago and you can relive that classic exchange by reviewing a post I wrote last month.

I've written so much on this subject that it would be virtually impossible to link to all of the pieces here, but as usual, I encourage anyone who's interested to start with the now classic Heisenberg Labrador posts (here and here).

The important thing to note is that proliferation of corporate bond ETFs like the iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF ( NYSEARCA:LQD ) or the iShares iBoxx $ High Yield Corporate Bond ETF ( NYSEARCA:HYG ) is in many ways reflective of a broader trend away from cash markets and into derivatives.

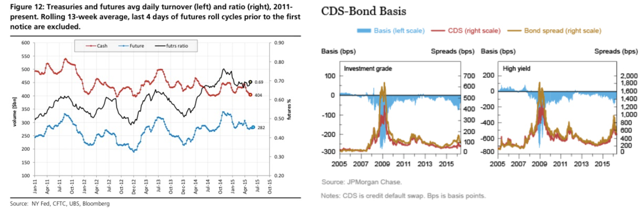

We've seen this in the rotation from cash bonds to single name CDS (and then from single name CDS into CDX) and from Treasurys into futures.

The bottom line is that the market believes there's more liquidity in derivatives than in cash markets. You can find an in-depth discussion of this dynamic here, and below, find one chart from UBS and another from the NY Fed that demonstrate the shift from Treasurys to futures and from cash bonds to CDS, respectively (note: the UBS chart is dated, but it still illustrates the dynamic):

(Charts: UBS, left pane; NY Fed, right pane)

Ok, now I'm going to quote from my own post (the first one linked above) on the way to setting up the Vanguard analysis. This is from my Monday night missive:

An ETF is a derivative. I don't care what anyone else tells you. And do you know what the proliferation of ETFs has catalyzed? That's right, a shift away from the actual markets for the assets that underpin the ETF units.

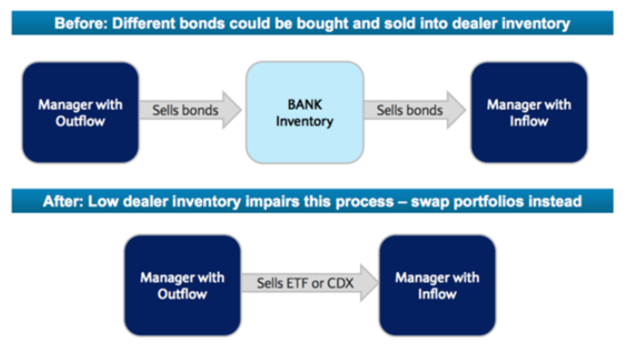

This is a disaster for the corporate credit market. The more investors and fund managers swap ETFs and portfolio products to match flows, the more illiquid the market for the underlying assets becomes. It's really simple. Here, look (the first flow chart is pre-crisis, the second, post-crisis):

Dealers (banks) can't serve as middlemen in the post-crisis regulatory regime (the cost of balance sheet is huge). So, there's essentially no market for the actual bonds that lay sleeping beneath the veneer of ETF liquidity.

Now then - and this part is critical - note that in the second chart above one side is "manager with outflow" and the other side is "manager with inflow." This is conceptually the same as "investor selling ETF", "investor buying ETF."

Well, what happens if the flows aren't diversifiable? What happens if they're unidirectional? What happens if everyone is selling and there's no dealer buffer?

I'll tell you what happens. Suddenly, the underlying bonds have to be sold to meet redemptions. Next comes the firesale.

Ok, so let's bring in Vanguard to "explain" why this is inaccurate.

I imagine that quite a few readers will immediately spot the problem with their reasoning. This is from a report that's amusingly called "ETFs: Clarity Amid The Clutter" (my highlights):

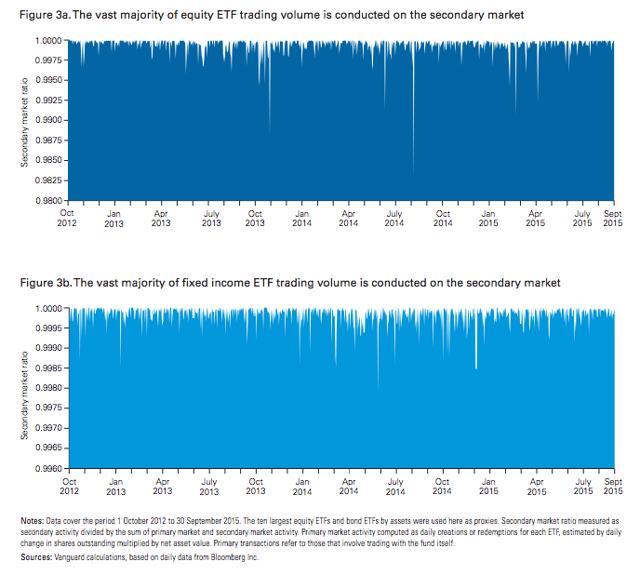

The overwhelming majority of [ETF] trading reflects secondary market transactions (i.e., trading of ETF shares between two market participants), and only a very small amount results in primary market trading (i.e., trading in the underlying securities market). The secondary market provides investors with an additional source of liquidity, meaning they can trade a broad portfolio of securities without trading in the underlying market.

Figure 3a shows the percentage of daily equity ETF trading volume conducted solely on the secondary market. The median ratio was 99%, suggesting that for every €1 in trading volume, only 1 cent resulted in primary market trading. Put another way, 99% of the trading volume resulted in no portfolio management impact and no trading in underlying securities (Figure 3b shows the same analysis for bond ETFs - the median ratio here was also 99%).

Did you spot the absurdity in there?

Vanguard is mistaking the problem for the solution.

First off, they are assuming diversifiable flows. That is, they are assuming sellers and buyers. We can go as deep into the ETF creation and redemption process as we want (and if you click on the Vanguard .pdf linked above they have a handy box that outlines the basics), but Vanguard and a whole lot of other folks out there seem to have a penchant for missing the forest for the trees.

That is, it stands to reason that if there's a large enough sell imbalance, there's going to be trouble at the end of the day. Read, for instance, the following (again from Vanguard) and ask yourself what might happen in the event everyone expects the value of the underlying bonds to plunge:

When falling demand for the ETF shares causes them to trade at a lower price (i.e., at a discount), an AP may buy shares in the secondary market and redeem them to the ETF in exchange for the underlying securities. These actions by APs, commonly described as "arbitrage activities", help keep the market-determined price of an ETF's shares close to the market value of the underlying assets.

I'm not entirely sure how willing broker-dealers would be to arb this in a panic.

And that speaks to the second point, which is that conceptually, when you stop using something, it falls into disrepair. In the context of markets, that means that the more you avoid trading the underlying securities, the more illiquid the market for those securities becomes.

It's common sense.

The more you rely on derivatives, the less you're trading the cash markets. The less you trade the cash markets, the more illiquid those markets become. The more illiquid the cash markets are, the more you turn to derivatives as a more liquid alternative. And around we go. The "solution" (migrating to derivatives) makes the original problem (a lack of liquidity in the cash market) that much worse.

So ultimately, I think perhaps Vanguard (and BlackRock) have, by virtue of their familiarity with the actual creation/redemption process, become blind to common sense.

That is, when you become an expert on something, there's a tendency to assume that people looking at it critically from the outside are clueless because they don't understand the mechanics like you do. But in fact, being in tune to the mechanics can make you blind to the bigger picture which outside observers still have a good handle on. I think that applies here.

In his discussion with Larry Fink, Carl Icahn said the following:

Obviously, for every seller, there's a buyer. So sort of obfuscation. You want to buy an ETF? There's a guy to sell ETF, of course. How the hell else do you buy it?

Well, at the end of the day, the reverse is true too. That is:

You want to sell an ETF? There's a guy to buy an ETF, of course. How the hell else do you sell it?

And see that's the problem. The way you sell it if there's no "guy" to buy it is to effectively force (and you wouldn't know you were doing this) the ETF to sell the underlying securities.

But because of the overreliance on ETFs, the market for those securities is completely illiquid.

That's where the problem is.

This article was written by

Perhaps more than any other time in the last six decades, the fate of markets is inextricably intertwined with the ebb and flow of geopolitics. It's become increasingly clear that one simply cannot fully comprehend market movements without a thorough understanding of concurrent political outcomes. Drawing on extensive experience in both politics and finance, Heisenberg will help demystify a world in which investors can no longer hope to conceptualize of markets as existing in anything that even approximates a vacuum.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Source: https://seekingalpha.com/article/4043448-how-you-sell-vanguard-misses-point-on-etfs

0 Response to "Is It Easy to Sell Vanguard Etf"

Post a Comment